At its heart, the formula for calculating your Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) is quite straightforward. You start with your Beginning Inventory, add any Purchases you've made during a specific period, and then subtract your Ending Inventory. The result is the direct cost of everything you’ve sold.

Simple, right? But what does that number actually tell you?

What COGS Reveals About Your Business Health

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the calculation, it's crucial to grasp what the COGS figure really represents. Think of it as the core cost of bringing your products to life.

For instance, if you run a small bakery in Manchester, your COGS would include the flour, sugar, and butter you use in your cakes. It’s the direct, tangible stuff. What it doesn't include are indirect costs like your shop's rent, marketing flyers, or the salary of your delivery driver.

Understanding COGS is non-negotiable because it’s the very first major expense you take away from your revenue. Once you've done that, you're left with your gross profit – a powerful indicator of how efficiently you're running your business and whether your pricing is on the right track.

The Foundation of Financial Clarity

Getting your COGS calculation spot-on is the bedrock of a clear financial picture. It’s not just about ticking a box for your accountant; it’s about arming yourself with the data to make smarter, more profitable decisions.

With a firm handle on your COGS, you can:

- Set smarter prices: If your COGS is creeping up too close to your sale price, your profit margins are getting squeezed. Knowing this number helps you price your products for genuine, sustainable growth, not just for turnover.

- Manage your inventory effectively: A rising COGS could be a red flag. It might mean your material costs are soaring, or your production process has become wasteful. It’s a clear signal to start looking for new suppliers or to find efficiencies you’ve been missing.

- Improve your strategic planning: Don't forget, investors and lenders are looking at this too. A well-managed COGS shows them you have a tight grip on your core operations, which builds confidence and can unlock future funding.

Ultimately, COGS creates a clean line between the cost of producing your goods and the cost of operating your business. This distinction is fundamental to seeing where your money is actually going and how effectively you turn raw materials into cash in the bank.

This single metric is the launching point for almost all other meaningful financial analysis. From here, you can dig into other key performance indicators, like figuring out what is gross profit margin by reading our detailed guide.

Nailing this calculation isn't just an accounting chore—it's a strategic necessity for any product-based business that's serious about long-term success.

Key Components of the COGS Formula

To make sure we're all on the same page, let's quickly break down the essential elements you'll need to calculate your Cost of Goods Sold.

| Component | What It Means for Your Business |

|---|---|

| Beginning Inventory | This is the total value of all your stock at the start of the accounting period. It's the same number as your ending inventory from the previous period. |

| Purchases | This includes the cost of all the new inventory you bought or produced during the period, including raw materials and any direct labour costs. |

| Ending Inventory | This is the value of all the stock you have left unsold at the end of the accounting period. A physical stocktake is often needed here for accuracy. |

These three figures are the pillars of the COGS calculation. Get them right, and you'll have a reliable, insightful metric to guide your business strategy.

Decoding The COGS Formula Components

The formula itself is straightforward, but applying it to a real business is where things get interesting. To really get a feel for how COGS works, let’s leave the theory behind and step into a small, UK-based craft gin distillery.

By putting some tangible figures to each part of the equation, you’ll see how the numbers truly come together. This isn't just about accounting; it's about understanding the real cost of your operations.

Beginning Inventory: Your Starting Point

First up is your Beginning Inventory. This is simply the value of all the stock you’re holding when the accounting period kicks off, whether that's a new quarter or a financial year.

For our distillery, this isn’t just the finished, bottled gin on the shelves. It’s everything that goes into making it. We're talking about:

- Raw botanicals like juniper berries, coriander seeds, and angelica root.

- The neutral grain spirit that acts as the gin's base.

- All the packaging materials – empty bottles, corks, labels, and even the wax for the seals.

Calculating this is easy. The value of your beginning inventory is just the ending inventory figure from the period you just closed. So, if our distillery wrapped up the last quarter with £20,000 worth of stock, that’s their beginning inventory for this new quarter. It’s a continuous, rolling figure.

Purchases: The Costs To Create And Acquire

Next, we have Purchases. Now, this term can be a bit deceptive. It’s not just about what you’ve bought; it covers all the direct costs you’ve sunk into your products during the period.

Think of it as the total investment you've made to create the goods you hope to sell. For our gin maker, that involves a lot more than just buying botanicals.

I often see people make the mistake of only including raw material costs under 'Purchases'. For a true COGS figure, you have to account for the direct labour and other production costs that were essential to turn those materials into a finished product.

So, the distillery’s 'Purchases' figure would need to include:

- Raw Materials: The cost of buying more botanicals, spirit, and water. Let's say this was £15,000.

- Direct Labour: The wages paid to the distillers who are actually operating the stills and making the gin. If this came to £8,000, it goes in.

- Production Overheads: Costs tied directly to manufacturing, like the electricity to power the stills or the specific cleaning supplies for the equipment. We'll add £2,000 for this.

- Inbound Freight: The shipping bill for getting those juniper berries from a supplier to the distillery, which was £500.

Add all that up, and the distillery’s total 'Purchases' for the period come to £25,500.

Ending Inventory: What’s Left Over

Finally, we land on Ending Inventory. This is the value of all the stock you have left, unsold, at the very end of the accounting period. To get this number, the distillery team has to do a physical stocktake, counting everything from sealed bottles of gin right down to the last bag of botanicals.

Let's imagine after counting everything up, they find they have £18,000 worth of inventory left.

This final number is crucial for two reasons. It’s the last piece of the puzzle for this period's COGS calculation, and it also becomes the beginning inventory for the next period, bringing us full circle.

Gathering Your Data for an Accurate Calculation

Let's be blunt: your COGS calculation is only ever as good as the numbers you feed into it. If your data is shoddy, your final COGS figure will be misleading, painting a completely false picture of your business's health and profitability.

To get it right, you need to be disciplined about tracking your financial information throughout the year. This isn't about a mad dash to find receipts come year-end; it's about building solid, reliable habits from day one.

Solidify Your Inventory Management

A precise COGS calculation lives and dies by your inventory management. Whether you’re using dedicated software or a carefully maintained spreadsheet, the goal is the same: you need an accurate, real-time view of your stock levels and their value.

A robust system will track every item from the moment it lands in your storeroom to the moment it's sold. This gives you a fantastic digital record, but you can't just take its word for it.

One of the biggest mistakes I see is businesses relying entirely on their software without ever physically checking the stock. Regular stocktakes are non-negotiable. They are the only way to reconcile what your system thinks you have with what's actually sitting on the shelves.

Running these physical counts—ideally quarterly, but monthly is even better—helps you catch problems like theft, damage, or simple admin errors early. If you wait until the end of the year, these small issues can become major headaches that throw your accounts into chaos.

Diligently Track Every Purchase

When we talk about 'Purchases' in the COGS formula, we mean more than just the price tag on your raw materials. To get an accurate number, you have to capture every single direct cost involved in getting your products ready to sell. This all comes down to organised record-keeping.

Make sure you're consistently tracking the following:

- Supplier Invoices: This is the big one. Keep a meticulous record of every invoice for materials and goods you buy.

- Shipping and Freight Costs: The cost to get that inventory to your business (sometimes called 'carriage inwards') is a direct cost and absolutely must be included.

- Import Duties and Taxes: Sourcing materials from overseas? Any customs duties or non-recoverable taxes you pay are part of that product's cost.

- Direct Labour Costs: You need to document the wages for any staff directly involved in making your products.

Keeping these records isn't just good business sense; it's a legal requirement. You can get a clearer picture of your obligations by reading up on what records you need to keep for your limited company accounts and for how long.

By making these practices a core part of your operations, you ensure that every number in your COGS formula is backed by solid evidence. This foundational work pays off, giving you financial reports you can actually rely on.

Choosing an Inventory Valuation Method

The value you assign to your inventory has a massive, direct impact on your final COGS figure. This isn't just some administrative box-ticking exercise; it genuinely affects your reported profit margins and, by extension, how much tax you'll owe. For businesses here in the UK, the method you pick has to be a fair reflection of how stock actually moves through your company.

To make this real, let's look at the two most common methods through the eyes of a coffee bean roaster. They buy beans regularly, and as you'd expect, prices are all over the place throughout the year.

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) Method

The First-In, First-Out (FIFO) method is built on a simple, logical idea: the first things you buy are the first things you sell. It makes perfect sense for perishable goods like coffee beans, where you'd naturally want to shift your oldest stock first to keep everything fresh.

Let's say our coffee roaster buys three batches of the same speciality beans over the first quarter:

- January: 100kg at £10 per kg (£1,000)

- February: 100kg at £12 per kg (£1,200)

- March: 100kg at £14 per kg (£1,400)

Now, imagine they sell 150kg of beans during that period. With FIFO, the cost is pulled from the oldest stock first. They'd use up the entire January batch (100kg at £10) and then dip into the February batch for the remaining 50kg (at £12).

The COGS calculation looks like this: (100 x £10) + (50 x £12) = £1,600. Your leftover inventory is then valued using the most recent purchase prices.

A key takeaway here is that during times of rising prices, FIFO gives you a lower COGS and, therefore, a higher gross profit on paper. This happens because you're matching older, cheaper costs against your current revenue, which can make the business look more profitable.

The Weighted Average Cost Method

The Weighted Average Cost (WAC) method takes a totally different route. Instead of obsessing over individual purchase costs, it smooths out all the price fluctuations by creating a single average cost for all identical items in your stock. It's often much simpler to manage, especially if you deal with large volumes of identical products where tracking specific batches would be a nightmare.

Let’s go back to our coffee roaster's purchases. First, we need the total cost and total quantity.

- Total Cost: £1,000 + £1,200 + £1,400 = £3,600

- Total Quantity: 100kg + 100kg + 100kg = 300kg

The weighted average cost per kg is simply £3,600 / 300kg = £12 per kg.

When they sell the same 150kg, the COGS calculation is dead simple: 150kg x £12 = £1,800. This approach gives you a blended cost, which helps shield your financial reports from the jolts of sudden price swings.

Understanding historical price shifts is crucial when making this choice. Remember, between September 2022 and March 2023, the UK endured seven straight months of double-digit inflation. It peaked at an eye-watering 11.1% in October 2022, which sent raw material costs through the roof for countless businesses. You can get a sense of these trends by looking at data on the UK's inflation rate.

Your choice of method is also tied to your wider accounting strategy. If you want to get a better handle on this, have a look at our guide explaining the differences between cash basis and accruals accounting. The most important rule? Consistency. Once you choose a method, you need to stick with it to make sure your financial reports are comparable from one year to the next.

Putting It All Together: A Worked COGS Example

Theory is one thing, but seeing the numbers in action is where it really clicks. Let’s walk through a complete, practical scenario to show you exactly how to calculate the cost of goods sold.

We’ll use a fictional UK-based online clothing boutique, ‘Willow & Weave’, for our example.

Setting the Scene: The Boutique's Figures

Willow & Weave sells artisan-made dresses and has just wrapped up its first quarter (January to March). Now, it's time to crunch the numbers and work out their COGS to see just how profitable the start of the year really was.

To get started, we need the three key figures we've discussed. After a thorough review of their accounts and a physical stocktake, the owner has gathered the following data:

- Beginning Inventory: On 1st January, the value of all their stock on hand (fabric, finished dresses, labels, packaging) was £15,000.

- Total Purchases: Over the quarter, they spent £25,000 on direct costs. This includes buying new fabric, paying their seamstresses, inbound shipping for materials, and ordering more branded packaging.

- Ending Inventory: On 31st March, after counting every last roll of fabric and unsold dress, they found the remaining stock was valued at £12,000.

With these three numbers, we have everything we need to plug into the COGS formula. It’s a simple case of adding the costs together and then subtracting what’s left.

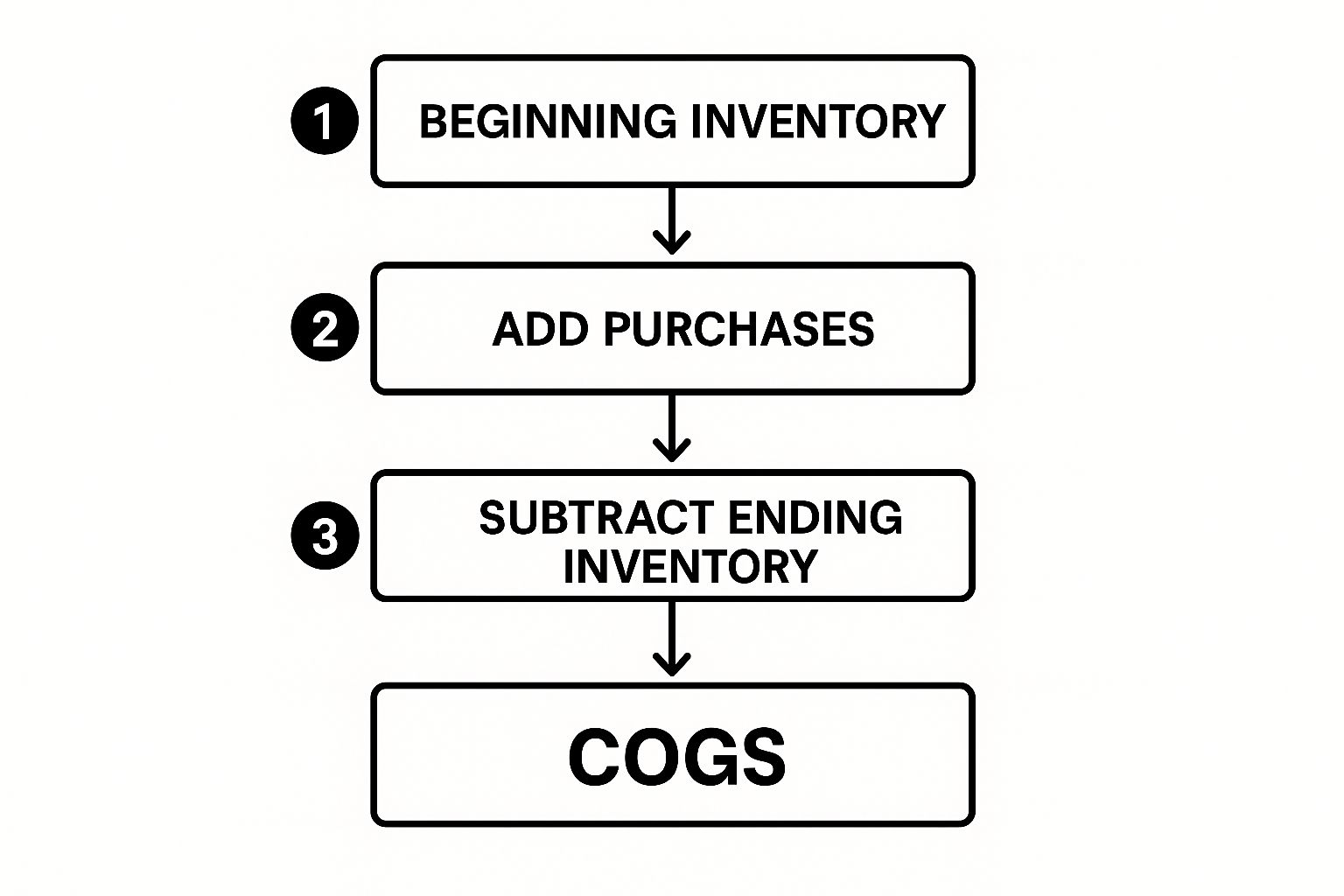

This visual breaks down the process quite nicely:

As you can see, you start with what you had, add what you bought, and then take away what you didn't sell. Simple.

The Final COGS Calculation

Right, let's put those figures into the formula we’ve been working with:

(Beginning Inventory + Purchases) – Ending Inventory = COGS

For Willow & Weave, the calculation looks like this:

** (£15,000 + £25,000) – £12,000 = £28,000 **

There we have it. The Cost of Goods Sold for Willow & Weave for the first quarter is £28,000. This figure represents the direct cost of all the dresses they actually sold during that three-month period.

It's vital to remember that external economic factors can heavily influence your 'Purchases' figure. For example, monitoring trends in the UK's Producer Prices Index (PPI) is a smart move. This index reflects what domestic producers are charging for their goods, giving you a heads-up on potential cost increases for your raw materials. You can explore more about how producer prices are trending in the UK to stay ahead of the curve.

What This Tells Us About Profitability

Knowing your COGS is crucial, but its real power comes when you use it to find your gross profit. This is where you see if your core business model is working.

Let's say Willow & Weave generated £60,000 in revenue during the same quarter. Now we can see their core profitability:

- Revenue: £60,000

- Cost of Goods Sold (COGS): £28,000

- Gross Profit: £60,000 – £28,000 = £32,000

This instantly reveals that for every pound of revenue, roughly 47p went directly into making the product. The remaining 53p is the gross profit left to cover all other business expenses like marketing, rent, and salaries.

This single, straightforward calculation provides a clear and immediate health check on the boutique's pricing strategy and production efficiency. It’s the first, most important indicator of financial performance.

A Few Common COGS Questions Answered

Even with the formula laid out, things can get a bit hazy when you start applying it to your own business. It's completely normal. Over the years, I've seen business owners run into the same stumbling blocks time and again, so let's clear up a few of the most frequent questions.

Getting these finer points right is what separates a vague guess from a truly accurate financial picture. It’s about being able to stand behind your numbers with confidence.

Should I Include Shipping Costs in COGS?

This one trips people up all the time. The short answer is: sometimes.

You absolutely should include the cost of getting materials or products to your business. This is often called freight-in or carriage inwards, and it's a direct cost of getting your stock onto the shelves. Think of it as part of the price you paid to have that inventory ready for sale.

But what about shipping products out to your customers? That’s a different beast entirely. Those costs are a selling expense, not a cost of the goods themselves. They belong under your operating expenses, well away from your COGS calculation.

What About Damaged or Obsolete Stock?

It’s an unfortunate part of business, but sometimes stock gets damaged, goes off, or simply becomes obsolete. When you realise you can't sell an item, you have to write it off.

When you write off stock, you're officially recognising its value as a loss. This write-down is usually included in your COGS for that period. The practical effect is that it increases your COGS figure and, as a result, lowers your gross profit.

This is exactly why doing regular stocktakes is non-negotiable. It helps you catch unsellable inventory early, so your financial records stay accurate and you're not carrying 'ghost' assets on your books.

How Does Inflation Affect My COGS Calculation?

Rising prices can throw a real spanner in the works. When the cost of your raw materials or stock goes up, it directly inflates the 'Purchases' part of the COGS formula. This pushes your total COGS higher and eats into your margins.

This has been a massive headache for UK businesses lately. In the 12 months to April 2023, UK food price inflation hit an eye-watering 19.1% – a high we hadn’t seen in over 45 years. This surge was fuelled by everything from energy bills to supply chain disruptions. You can dig deeper into the UK food price inflation findings to see the full impact.

When external pressures like this are squeezing your business, tracking your COGS accurately isn't just good practice; it's essential for survival.

Navigating these complexities is where having an expert in your corner really pays off. At Stewart Accounting Services, we help businesses across the UK get a firm grip on their finances, turning confusing calculations into clear, powerful insights. Find out how we can help at https://stewartaccounting.co.uk.